Illustration by Andrew Strawder

In late autumn of 1964, Wong Jack Man piled into a brown Pontiac Tempest with five other people as the sun set on San Francisco Bay. The group departed Chinatown and traveled east over the Bay Bridge to Bruce Lee’s new kung fu school on Broadway Avenue in Oakland. After weeks of back-and-forth messages and rising tensions, high noon had finally arrived.

The showdown that occurred that night in front of just seven people behind locked doors was a legendary matchup by just about any standard. It posited two highly dynamic 23-year-old martial artists who shared a compelling—almost yin/yang-like—symmetry between them: the quiet ascetic and the boisterous showman, traditional against modern, San Francisco vs. Oakland, Northern Shaolin against Southern. The fight that ensued would affect the remainder of both of their lives. And even still, this symmetry would persist: one would silently endure the fight’s long shadow for decades, while the other would boldly become a global icon before passing all too soon.

Far more than just some youthful clash of egos, the incident has a much wider relevance. Not only did it shape the fighting approach of the man who would become the world’s most famous martial artist, but the match itself was a key moment in a battle of paradigms. If Bruce Lee is indeed a philosophical godfather of modern mixed martial arts competitions, then his fight with Wong Jack Man was a qualifying moment, a crucible that tested the validity of martial techniques much in the way that early UFC fights would in the late 90s, tearing back the curtain to bluntly expose what was effective and what was mere hype.

Yet this context has mostly gotten lost in the shuffle over the past half-century, as the showdown seems to permanently teeter between absurd urban mythology and obsessive hero worship of Bruce Lee. With Hollywood gearing up to release its latest sensationalized rendering of the fight, a new wave of misinformation is already starting to take hold. George Nolfi’s hyperbolic new film Birth of the Dragon will frame Wong Jack Man as a Shaolin Monk on pilgrimage who eventually teams up with Lee to battle the mafia. This movie will file in alongside the often-maligned 1993 biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which framed the fight as a dungeon battle in front of some kind of elder ninja counsel, concluding with Wong cheap-shot kicking Bruce in the spine.

By simple contrast, the factual history is infinitely more compelling than the mythology.

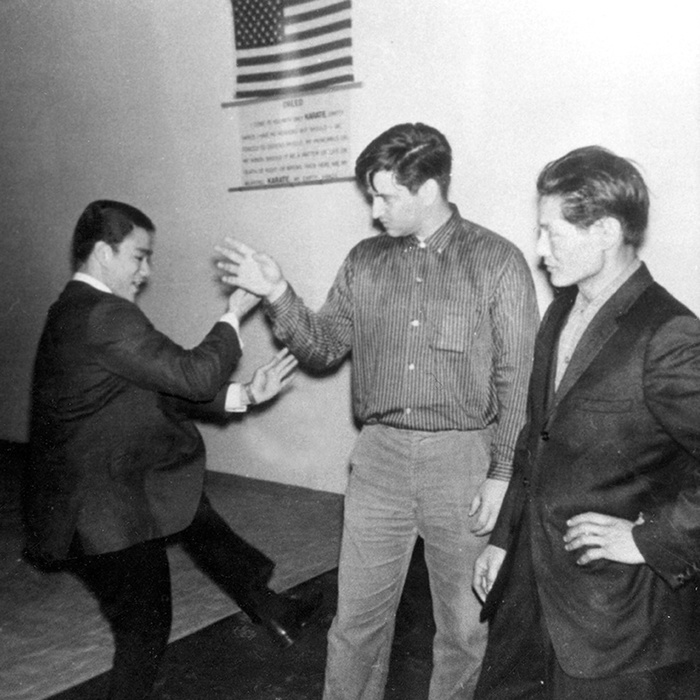

A young Bruce Lee with key Oakland-era colleagues Ed Parker (center) and James Lee in Ralph Castro's kenpo school in November of 1963. Bruce had found a very likeminded group of martial artists within James Lee's orbit in Oakland, and would soon relocate from Seattle to continue collaborating with them. (Photo courtesy of Greglon Lee)

Oakland

By the early 1960s, the San Francisco Bay Area was home to a robust martial arts culture that was populated by a diverse array of talented practitioners, who hailed from southern China, Hong Kong and Hawaii. Bruce dropped out of college, and abruptly left a good situation that he had built for himself in Seattle, to participate in this pioneering scene in the Bay Area.

Most notably, he took up residence in the city of Oakland to collaborate with James Lee (no relation), a blue collar local who was twice Bruce’s age, who had a lingering reputation for his youthful days as a no-nonsense street fighter and body builder. Yet James was also a brilliant innovator for the martial arts in America, and was already enacting the sort of martial arts future that Bruce was just beginning to envision. James was publishing his own books, designing his own workout equipment, and running a very modern training environment out of his garage. He quickly introduced Bruce into his orbit of talented and progressively-minded colleagues, which included innovative jujitsu master Wally Jay and early American kenpo karate pioneer Ed Parker. In 1963, James would produce Bruce’s first book—Chinese Gung Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self-Defense—through his self-run publishing company.

Altogether, Bruce very much found what he had wanted in Oakland: a unique martial arts think-tank laboratory where he could practice and discuss martial arts 24/7 among experienced and likeminded collaborators. These Oakland days encapsulated key milestones in Bruce’s life, including the creation of the only book he ever published in his lifetime, getting noticed by Hollywood, his fight with Wong Jack Man, and his initial development of Jeet Kune Do. However, this era typically gets minimal attention in most biographical works, despite its formative significance. In keeping with that trend, Birth of the Dragon will not only omit the likes of James Lee from its storyline, but also completely drop Oakland from this history, and instead set the entire era within San Francisco, where things were very different for Bruce.